How do we find what we are looking for? And how do we do it?

Visual search deals with the problem of how we find what we are looking for (relevant things) in a world full of things that might also be irrelevant to us.

Visual search is necessary for our daily life. Imagine we have to process all the information in our visual field at once. It is simply not possible because of our limited cognitive capacity. Visual search is also very important for design.

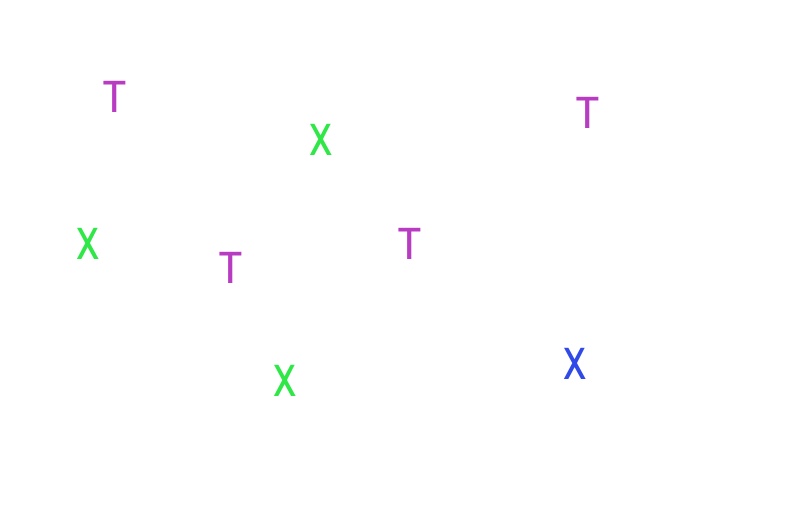

See this example:

Feature Integration Theory by Treisman and Gelade (1980) might explain phenomena like this. For example, often, I accedentially tap the wrong App Icon when I want to open Face Time App. It happens when we try to find a specific app but several apps share the same color feature:

What is happening here? According to Feature Integration Theory, first, basic visual features like the color or shape of any object are detected and processed *automatically* (this means also rapidly) on a pre-attentive stage whereas attention is then needed afterward to combine the features so we can perceive the object. This attentive stage needs more time (due to information processing) than the first automatic process.

Let’s try it: First, find the blue X, which is our feature target (=feature condition)

That was pretty easy, right?

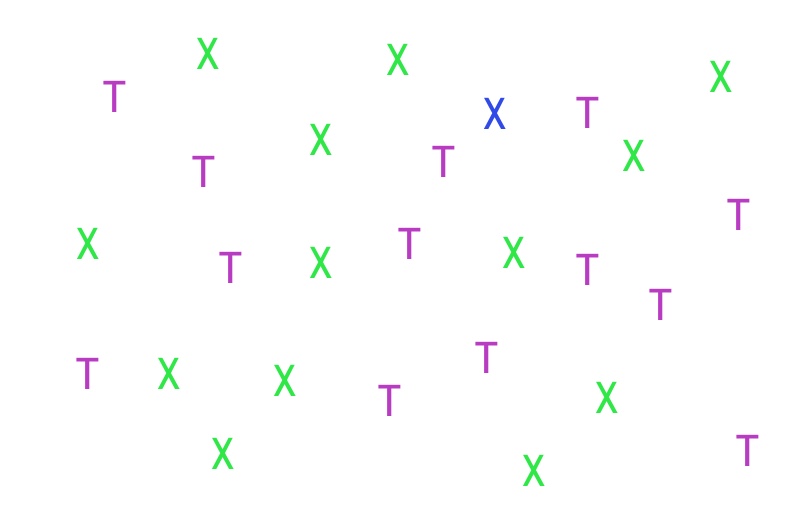

Try again on this one with more distractor items:

We see, even with more distractors, the blue X appears to “pop-out” which allows you to detect it very fast. You are looking at all the objects at once and you are still able to detect the blue X fast. It’s fast because we use automatic, parallel processing: We just look at the visual field and the target “pops out” on us because of its unique feature – the blue color – which is not shared with any of the other items around.

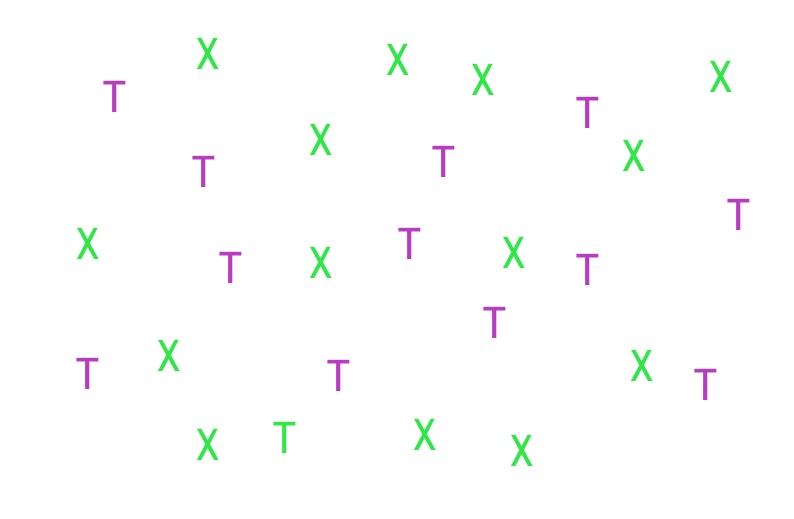

Now let’s try the attentive stage (“conjunction condition”): Look for a green letter “T”

This probably took longer, right? Since we are no longer searching for only one feature (color OR shape) our target object doesn’t “pop out” anymore.

The search appears much harder because it is surrounded by other green letters and other “T’s“. Our target object (the green T) shares a feature with all of our distractor objects (the green color of the letter X & the shape with the purple “T” ).

Therefore you have to look at each object and you use directed attention in combining the features. So, we scan each object and if it is not our target object (Feature 1 = green/color plus Feature 2 =T/shape) we move on to the next object to check until we spot our target. This equals a serial, step-by-step processing, or a serial search process. You have to check each item/object with directed attention. That takes time.

What does that mean?

We see that in the first conditions (the feature conditions) that search time is not affected by the number of distractors. The target “pops out” and it is detected automatically on a pre-attentive stage. We do not need attention to detect our target object, instead, we use parallel processing/ parallel search.

But in the conjunction condition, the search time is increased because we have to use directed attention to carefully check against the distractor items which results in serial processing / serial search.

Search time will also increase with the number of visible distractor items.

An example straight out of my kitchen which might have some effects on my meals:

Garlic and cinnamon share the same package design. The color is the same. The only difference is the text on the label. What could go wrong? :D

That means I have to read the label carefully each time or I have to put the cinnamon at another place without any conjunction distractors.

What does that mean for design?

Too many objects that share features might make it harder for people to find what they are looking for. Remember the example with the google icons? That’s just the effect: We might find it difficult to differentiate between options. That can be dangerous in situations where fast action is required, e.g. in the healthcare context, automotive interfaces, or industrial context. But even for product designs that won’t be used in safety-critical environments, we can use basic cognitive psychology research to make life easier for many people.

Further reading Treisman, A. M., & Gelade, G. (1980). A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology, 12(1), 97–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5

Schreibe einen Kommentar